Links » Abdelkader Biography and Spirituality » A Muslim Healer For Our Time

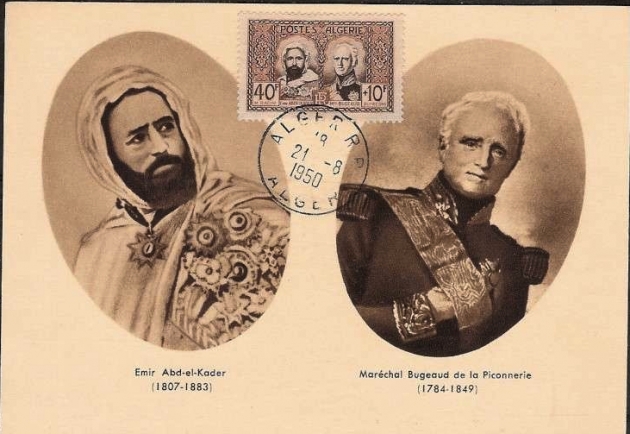

A Muslim Healer For Our TimeJohn W. Kiser  March 7, 2017 In the spring of 1860, Col Charles Henry Churchill was well into his interviews with one of the great personalities of his era. As a British military officer and former diplomatic representative in Damascus to the Ottoman Empire, Churchill finally found the opportunity to record first-hand the extraordinary life struggle of Emir Abdelkader al- Jazairy (the Algerian) who was living in exile under watchful French eyes. Since the early 1830s the emir’s jihad to contain French colonial ambitions in North Africa won him admirers around the world, even as far as the Missouri Territory. A frontier lawyer named Timothy Davis even named a settlement in his honor in 1846 shortened to Elkader, today the county seat of Clayton County, Iowa. Abdelkader’s resilience and chivalrous behavior on and off the battlefield, and his humanitarian treatment of French prisoners essentially turned him into a David versus Goliath figure in the eyes of many. By 1847 a determined French commitment to dominate all of Algeria convinced him that further resistance would cause useless suffering of his own people. Once believing he was doing God’s work by leading the jihad, the emir argued with his council that God must want France to have its turn to rule. Abdelkader negotiated an armistice agreement that was approved by the governor of Algeria, the youngest son of King Louis Philippe. In sum, the Emir and his extended family would be taken to the Middle East. In turn, Abdelkader gave his word that he would never return to Algeria or make trouble for France. Fifteen years of experience in peace and war with the emir had taught the French generals in the field one thing: Abdelkader was an honorable opponent who considered his word to be sacred. Churchill admired the emir first as a resilient and wily warrior-statesman, and then as stoic prisoner who was betrayed within months of his submission by a change of government in France, leading to a five year detour. Before Churchill finished his interviews, the emir’s fame rose to new heights. This time it would be as a courageous humanitarian honored by heads of state around the world, a hero for his faith, and even adopted by French, Syrian and American Masonic lodges. On July 6 1860, Churchill witnessed the governor in Damascus’s punish Christians who were no longer paying the head tax. Abdelkader and his sons organized the rescue and protection of thousands in the neighboring Christian quarter, even offering bounties for Christians brought safely to his enormous French paid residence. Around 10,000 were saved over several days, many then escorted to Lebanon with protection. Letters of gratitude poured in from around the world, one of which was from Bishop Louis Pavy in Algiers, to which the emir responded: His most valued letter, however, came from fellow freedom fighter, Emir Shamil, living under house arrest in Moscow: “May the laurels of distinction always bear fruit for you...you have put into practice the words of the Prophet (to protect the innocent and minorities) and set yourself apart from those who reject his example. May God protect us from those who transgress His Law.” Indeed, false religion can produce monsters – and so can false patriotism. Humans can become monsters and they come in all nationalities, races, and religions. Deranged by zeal of bitterness and false teaching, they can become ticking time bombs. What, however, are their triggers? Abdelkader’s mother, Zohra, often warned that ritual purity was only half of faith, and that the harder half – to purify one’s inner self – was sorely forgotten. A true instrument of God’s will restrains egotistical desires and violent passions of anger, envy and revenge: what the Prophet Mohammad called the greater jihad and Catholics called the seven deadly sins. By resisting his fanatical ‘dead-enders’, convincing them to lay down their arms and spare their families from imprisonment or death, Abdelkader had waged the greater and truer Jihad. Amongst a plethora of life experiences, skills, and principals, Abdelkader believed foremost that the pursuit of knowledge was the highest good and ultimate purpose in life, for knowledge ultimately leads to right conduct. But his was a world of hierarchy. Social relations were hierarchical, and so too was knowledge. In his famous Letter to the French written in 1856, the emir laid out his understanding of what made man different from the rest of creation : love of knowledge, pursuit of truths that transcend the senses – truths of mathematics, geometry, philosophy, the moral truths. The most important knowledge is political. Why? He believed man is a social animal who needs to cooperate to survive. No knowledge is more important than that needed for living in and engaging with political society, thus guiding human behavior justly. Such justice requires access to higher wisdom, transmitted via the prophets--vessels for mediating God’s wisdom. Nor is there any contradiction between them. They all subscribe to the fundamental moral rule: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. No religion owns God, yet they have a common message – glorify God and show compassion for His creatures. There is evidence that his story can inhibit radicalization, especially in young Muslims. Mohammad Sammak, advisor to the grand Mufti of Lebanon, stated in 2011: “The spirit of Abdelkader is the spirit of liberal and tolerant Islam. I believe we Muslims should do something together to revive Abdelkader’s spirit to guide our societies out of the tunnel. Pakistani scholar and editor of al Sharia, Mohammed Khan Nasir wrote to me after reading about Emir Abdelkader for the first time: He is not only a symbol of the Muslim concept of resistance and struggle against foreign domination, but an embodiment of true theological and rational ideas taught by Islam. His life story has been used by madrasas since 2011 to discuss the true meaning of jihad—to live righteously and control unruly interior spirits.” What, then, makes him applicable to forming counter-narratives of modern Jihad? First, he was simultaneously “local” and “universal.” He was deeply and authentically a pious Muslim (which means one who submits). Yet his religion wasn’t a safety belt holding his identity together, but a platform for probing the meaning of God’s creation. He also grew spiritually, especially during French imprisonment, where he saw the goodness in France and experienced the goodness of Christians and non-believers alike. His Islam made him bigger not smaller. He was a unifier and a reconciler. The plurality of beliefs was, to him, a reflection of the infinite nature of God and the inexhaustible ways to praise God. He didn’t see any conflict between politics, religion and science. Politics should be governed by a desire to guide people to live in harmony; religion should provide a common moral base of shared values and common origin. Science will teach us to grasp the basic unity of mankind. Finally, his was a life of virtue in action. True leadership requires a value system akin to the Cardinal Virtues of the Christian world, which Abdelkader possessed in abundance: a strong intellect capable of making distinctions, moral courage which includes compassion, justice and self-control. The emir’s behavior followed the now forgotten foreign policy philosophy enunciated in 1797 by President George Washington during his farewell address “…Observe good faith and justice toward all nations. Cultivate peace and harmony with all…. Religion and morality require it.” Washington did not say “with democracies” only, with “Christian countries” only. Perhaps he instinctively knew the wisdom of the Koranic verse: “If God wanted, he could have made us all the same, instead God created different tribes and nations so they might learn to know one another and compete in good works.” Fikra Forum is an initiative of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. The views expressed by Fikra Forum contributors are the personal views of the individual authors, and are not necessarily endorsed by the Institute, its staff, Board of Directors, or Board of Advisors. منتدى فكرة هو مبادرة لمعهد واشنطن لسياسة الشرق الأدنى. والآراء التي يطرحها مساهمي المنتدى لا يقرها المعهد بالضرورة، ولا موظفيه ولا مجلس أدارته، ولا مجلس مستشاريه، وإنما تعبر فقط عن رأى أصاحبها |